by Rod Smith, rodsmith@rodsbooks.com

- Efi File Editor

- Windows Efi Editor

- Efi Profile Editor Download

- Efi Profile Editor Free

- Efi Profile Editor Online

Originally written: 2/22/2015; last update: 3/11/2021

The EFI Shell is a 'shell' (think of a command prompt or a terminal shell) that a (U)EFI 'BIOS' can directly boot into (instead of your OS) allowing control and scripting of many items including booting scenarios. Step 3: Using your CB Quick Tune EFI Software A) A profile was programmed into your EMS by a CB EFI Tech before shipment of your kit. Then type in the following command. Sudo efibootmgr -o. And append the boot order to the above command. Sudo efibootmgr -o 0013, 0012,0014,0000,0001,0002,0003,000D,0011,0007,0008,0009,000A,000B,000C,000E. Let’s say you want 0012 to be the first boot entry. All you have to do is move it to the left of 0013 and press Enter. Custom UEFI and BIOS utilities for Aptio and AMIBIOS simplify the development and debug experience. AMI’s Aptio firmware offers an easy transition to the Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) specification, giving developers all the advantages of UEFI – modularity, portability, C-based coding – while retaining easy-to-use tools that facilitate manufacturing and enhance productivity.

This Web page is provided free of charge and with no annoyingoutside ads; however, I did take time to prepare it, and Web hosting doescost money. If you find this Web page useful, please consider making asmall donation to help keep this site up and running. Thanks!

| Donate $1.00 | Donate $2.50 | Donate $5.00 | Donate $10.00 | Donate another value |

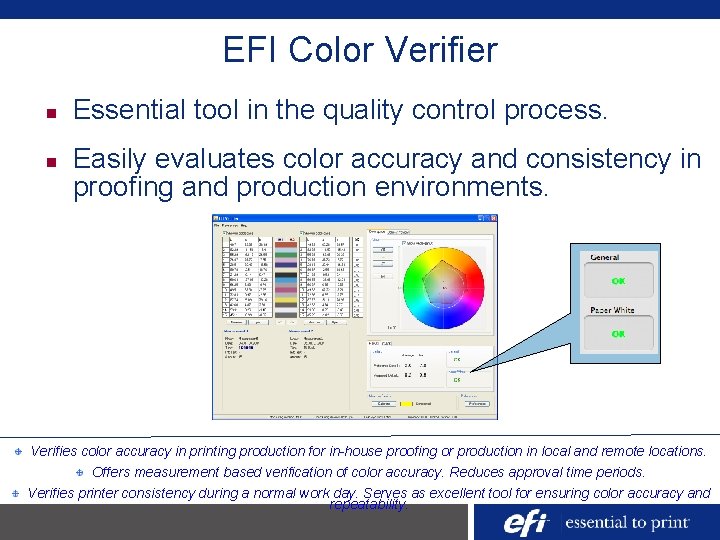

The comprehensive Fiery® Color Profiler Suite extends the capability of Fiery-driven printers with the most advanced colour management tools available, integrated at every stage of the printing workflow to ensure that colour reproduction is always accurate, consistent and repeatable. Contact us for more information about EFI Color Profiler Suite.

This page is part of my Managing EFI Boot Loadersfor Linux document. If a Web search has brought you to this page, youmay want to start at the beginning.

This page is the second of two covering Secure Boot as part of my EFI Boot Loaders for Linux document. If you're a beginner to intermediate user who wants to get Secure Boot working quickly with a popular distribution such as Ubuntu, Fedora, or OpenSUSE, I recommend you begin with my first Secure Boot page, Dealing with Secure Boot. This page is written for more advanced users who want to take full control of their Secure Boot features. Reasons to take this type of control are covered in the Why Read This Page? section of this page. The Contents section to the left shows other sections, in case you know enough to know what you want to read.

Contents

- Securing One Computer

Why Read This Page?

If you boot nothing but Windows, chances are this page won't do you any good, except perhaps to help satisfy your curiosity about the inner workings of Secure Boot. If you dual-boot Windows and a single popular Linux distribution such as Fedora or Ubuntu, you probably don't need this page, either; such distributions ship with Secure Boot solutions that work reasonably well for such dual-boot configurations. If your needs are more complex, though, you may find this page of interest.

Secure Boot works by using a set of keys embedded in the computer's firmware. These keys (or more precisely, their private counterparts) are used to sign boot loaders, drivers, option ROMs, and other software that the firmware runs. Most commodity PCs sold today include keys that Microsoft controls. In fact, Microsoft's keys are the only ones that are more-or-less guaranteed to be installed in your firmware, at least on desktop and laptop computers. Thus, to install your favorite Linux distribution, you must disable Secure Boot, find a Linux boot loader that's signed with Microsoft's keys, or replace your computer's standard keys with ones that you control. This page is about this final option, but both of the other options have their merits. Disabling Secure Boot is quick and enables you to easily run any EFI tool you like—but it also leaves you vulnerable to any pre-boot malware that might crop up. Using a pre-signed boot loader, such as the popular Shim program, can be even easier than disabling Secure Boot—if your distribution provides such a program. If not, you'll need to jump through hoops. Also, using a pre-signed boot loader with the default key set means that your computer will accept as valid Microsoft's boot loaders and any others that Microsoft decides to sign.

Taking control of your computer's Secure Boot keys offers several advantages over these approaches:

Efi File Editor

- Locking out threats from the standard keys—In theory, Secure Boot should prevent malware from running. On the other hand, it's always possible that an attacker could trick Microsoft into signing malware; or signed software could have bugs, such as the Boot Hole bug discovered in 2020 and described later, in Revoking Keys and Hashes. If you use Shim with the default keys, your computer will remain vulnerable to these threats, at least until they're discovered and your blacklist database is updated.

- Locking out threats from your distribution's keys—Similar to the preceding, it's also possible that your distribution's keys could be compromised, in which case an attacker could distribute malware signed with the compromised keys. Depending on how you manage your keys, you can greatly reduce this vulnerability—but the greatest level of protection will require extra effort on your part.

- Eliminating the need for MOKs—The Shim and PreLoader tools both rely on Machine Owner Keys (MOKs), which are similar to Secure Boot keys but easier to install. Because they can be more easily installed, it's conceivable that they could be more readily abused by social engineering or other means. Eliminating MOKs may therefore slightly increase your security, particularly if you're managing a collection of desktop computers used by other people.

- Taking philosophical control—Relying on a third party's keys strikes some people as being wrong. Partly this is because of the preceding reasons, but some people object to the dependency on a more philosophical level. If you fall into this category, generating and using your own keys may be appealing.

- Testing and development—If you want to develop your own boot manager, you may need to be able to test a signed version of your software in an environment that mimics a 'stock' computer. The process for signing binaries with Microsoft's Secure Boot keys is tedious and time-consuming, though, so you may need to set your computer up with your own keys so that you can sign the binaries yourself. When the software works as you expect, you can send it to Microsoft to be signed.

- Enabling Secure Boot on systems without keys—Some servers ship without Microsoft's Secure Boot keys installed. Using Secure Boot with such a server requires adding keys as described on this page. Note that Linux distributions for exotic platforms, such as ARM64, have acquired signed Shim implementations only relatively recently—Ubuntu 20.04 ships with a signed ARM64 Shim, for instance, but Ubuntu 18.04 does not. Thus, you may need to take this approach if you want to use Secure Boot with some exotic hardware.

- Overcoming boot coups—This one is admittedly speculative. Some people have reported difficulty getting their computers to boot anything but Windows by default; they can boot to Linux temporarily, use efibootmgr to set Linux as the default boot loader, but then find themselves booting back to Windows because the firmware keeps setting Windows as the default. If the Linux boot entry remains in place but is 'demoted,' setting your own boot keys might enable you to control this problem by removing Microsoft's key from the regular Secure Boot list and adding it to your MOK list. You'd need to use Shim or PreLoader for this to work. Note, however, that some computers hang upon encountering the first Secure Boot error; and if the problem is caused by a computer 'forgetting' its entire boot list, this solution will do no good whatsoever.

Of course, there are drawbacks to this approach, too. Some of these disadvantages are fairly obvious, but others may hide out and bite you unexpectedly:

- Extra setup effort—The length of this page is a hint of the lengths to which you'll have to go to make this approach work. I've tried to be as thorough as possible in writing this page, but nonetheless, you'll almost certainly find it easier to disable Secure Boot or use Shim or PreLoader, at least if your needs are modest.

- Lack of support for option ROMs—Some plug-in cards have firmware that's signed by Microsoft's keys. Such a card will not work (at least, not from the firmware) if you enable Secure Boot without the matching public key. (The card should still work once you've booted an OS. The biggest concern is for cards that must work in a pre-boot environment, such as a video card or for PXE-booting a network card.) You can add Microsoft's keys back to the environment to make such cards work, but this eliminates the advantages of not having those keys, if that's a significant factor for you.

- Greater potential for future problems—OS installation utilities and system upgrade tools may not run or may replace your working custom-signed boot programs with versions that are signed improperly for your system. You'll have to be alert to such potential problems and keep suitable backups for restoration purposes. Disabling Secure Boot may be necessary to install a new OS.

- Broken Secure Boot authentication—Some of my Secure Boot computers reject a significant fraction of EFI programs that are signed as described on this page. Other computers accept the same binaries just fine, and they work fine on the affected machines when launched via Shim, so it appears that either some computers' Secure Boot implementations are overly strict or there's a subtle problem in the way the binaries are signed that affects only some Secure Boot implementations. Binaries built with recent versions of GNU-EFI seem to be particularly prone to these problems. Of course, you might not run into such difficulties, but if you do, you may need to use Shim or PreLoader to overcome them.

If any of these advantages sounds compelling to you, read on. If the drawbacks sound like too much hassle, you may be interested in simpler ways of handling Secure Boot, as described on my Dealing with Secure Boot page.

Knowing Secure Boot Key Types

Before delving into the nitty-gritty of setting things up, you should be aware of the fact that there are four types of Secure Boot keys built into your firmware, and a fifth that you may encounter if you use Shim or PreLoader:

- Database Key (db)—This is the key type that you're most likely to think of with respect to Secure Boot, because it's used to sign or verify the binaries (boot loaders, boot managers, shells, drivers, etc.) that you run. Most computers come with two Microsoft keys installed. Microsoft uses one of these itself and uses the other to sign third-party software, such as Shim. Some computers also come with keys created by the computer manufacturer or other parties. Canonical (the creator of the Ubuntu Linux distribution) arranged for its key to be embedded in some computers' firmwares beginning early in the 2010s, for instance. As this description implies, the db can hold multiple keys—an important fact for some purposes. Note that the db can contain both public keys (which are matched to private keys that can be used to sign multiple binaries) and hashes (which match individual binaries). For the most part, this document focuses on the db as a carrier for keys, but you can add hashes to your db if you like. (The KeyTool program is useful for this purpose.)

- Forbidden Signature Key (dbx)—The dbx is a sort of anti-db; it contains keys and hashes that correspond to known malware or otherwise undesirable software. I don't describe setting up the dbx on this page, although you could install keys or hashes to it just as you would to the db. If a binary matches a key or hash that's in both the db and the dbx, the dbx should take precedence. This enables blocking a single binary (via its hash) even if that binary is signed by a key that you don't want to revoke because it's been used to sign lots of legitimate binaries.

- Key Exchange Key (KEK)—The KEK is used to sign keys so that the firmware accepts them as valid when entering them into the database (either the db or the dbx). Without the KEK, the firmware would have no way of knowing whether a new key was valid or was being fed by malware. Thus, in the absence of the KEK, Secure Boot would either be a joke or require that the databases remain static. Since a critical point of Secure Boot is the dbx, a static database would be unworkable. Computers often ship with two KEKs, one from Microsoft and one from the motherboard manufacturer. This enables either party to issue updates.

- Platform Key (PK)—The PK is the top-level key in Secure Boot, and it serves a function relative to the KEK similar to that of the KEK to the db and dbx. UEFI Secure Boot supports a single PK, which is generally provided by the motherboard manufacturer. Thus, only the motherboard manufacturer has full control over the computer. An important part of controlling the Secure Boot process yourself is to replace the PK with your own version.

- Machine Owner Key (MOK)—A MOK is equivalent to a db key; it's used to sign boot loaders and other EFI executables or to store hashes corresponding to individual programs. MOKs are not a standard part of Secure Boot, though; they're used by the Shim and PreLoader programs to store keys and hashes. As such, this page doesn't cover them in any detail.

All of these key types are similar; they're examples of Public Key Infrastructure (PKI), in which two long numbers are used for encryption or (in the case of Secure Boot) authentication of data. In Secure Boot, one key, known as the private key, is used to 'sign' a file (an EFI program). This signature is appended to the program. The other key, known as the public key, must be publicly available—in the case of Secure Boot, it's embedded in firmware or stored in NVRAM. The public key can be used, in conjunction with the signature, to verify that the file has not been modified and to verify that it was signed with the key matched to the public key in use.

Obviously, the public key is not sensitive; it needn't (and in fact it mustn't) be hidden away or kept secret. The private key, however, is sensitive; if it were to fall into the hands of a malware author, that person could sign malware that would then be accepted as valid by computers using the matching public key.

When you replace your computer's set of public keys with your own, you'll also create a set of private keys. You must keep these keys secure. Ideally, you should store them on an encrypted external medium locked in a safe. Of course, you must balance security of your keys with access; if you need to sign binaries every five minutes, keeping your keys in an off-site safe will be impractical.

The keys are stored in computer files, and each of the key types just described takes an identical form; in fact, you could use a PK as a MOK if you liked. Keep in mind also that each key is really two paired keys. Sometimes writers (myself included) get a little sloppy and write something like 'the binary was signed by the key in the firmware,' when in fact the binary was signed by the private key matched to the public key in the firmware.

Because of the discovery of the Boot Hole vulnerability, Shim has acquired its own built-in dbx-like database of forbidden keys and hashes. This is important because it complicates your choices; if you take full control of your Secure Boot keys with the intent of not using Shim, but if you enroll the public key for your chosen distribution in your db, your computer may run software that has known security flaws and that would be blocked from running by the Shim-dbx. This issue is covered in more detail later on this page.

Creating Secure Boot Keys

Now to action! The first step to replacing your computer's standard set of keys is to generate your own keys. To do this, you'll need several packages installed on your Linux computer. In particular, you need openssl and efitools. The former is available in a package of that name on most distributions, but efitools is less common. It's available in Ubuntu's repository, and builds for several distributions are available at the OpenSUSE Build Service (OBS). If necessary, you can compile it from source code; check here for source. Note that efitools is dependent upon sbsigntool (aka sbsigntools), so you may need to install it, too. See here for sbsigntool source code.

You must create three Secure Boot key sets (public and private), and for greatest flexibility, you'll need several file formats—annoyingly, different programs require different file formats. Generating all these keys requires running a number of commands. To help out, I've written a short script for this purpose; you can download it here, or copy-and-paste it from the following listing into a file (I call it mkkeys.sh):

Be sure to set the executable bit on the program file (as in chmod a+x mkkeys.sh). Running this program creates output similar to the following:

This script prompts you for a common name to embed in your keys. You can leave this blank if you like, but providing a name will help you identify your keys and differentiate them from other keys.

Be aware that you might not need to run this command, though; the procedure described for Securing Multiple Computers, which uses a program called LockDown, will build a new set of keys. By default there will be no common name in the keys created for LockDown, though. It's possible to embed the keys generated with the mkkeys.sh script in LockDown, if you prefer to use one key set for multiple procedures.

After running mkkeys.sh, you'll have a total of seventeen key files for PK, KEK, and DB. Filename extensions are .crt, .cer, .esl, and .auth for public keys and .key for private keys. The myGUID.txt file holds a GUID that's embedded in the .esl and .auth files. (The script calls python3 to generate this GUID. You may need to change the name of the Python interpreter on some systems. If myGUID.txt is empty, you should look into this detail.) As the script's message notes, you should copy the .cer, .esl, and .auth files to a FAT partition or USB flash drive that your target computer's EFI can read.

At this point, it's worth considering precisely how you intend to lock down your computer. Broadly speaking, you have three options:

- Extreme self-reliance — You can rely exclusively on your own keys, which means you must sign every program your firmware runs, and probably sign every Linux kernel you boot. This is an extreme solution that's likely to be tedious to maintain; but if you secure your private keys well, it can provide excellent security.

- Trusting some third parties — You can add third-party keys to your db, which will enable binaries signed by that party to run without modification. You might do this to simplify maintenance of a distribution such as Fedora, OpenSUSE, or Ubuntu, all of which distribute signed copies of GRUB and of their Linux kernels. Similarly, you might add one or both of Microsoft's public keys if you want to run Windows or third-party programs signed by Microsoft's key. (Note that plug-in cards may have firmware that's been signed by Microsoft's third-party key.) On the other hand, relying on these keys will render your computer at least theoretically vulnerable to attack should their private keys be compromised or should bugs, such as Boot Hole, be discovered in software signed by them. Because GRUB 2 flaws are likely to be handled via Shim's internal dbx-like database moving forward, launching GRUB 2 without Shim is becoming a bit risky.

- Hybrid with Shim — You can take partial or complete control of your Secure Boot keys by using your own PK, KEK, and perhaps db keys, and optionally add Microsoft's db keys as well; but rely on Shim (signed with Microsoft's keys or your own) to add its built-in keys with which to launch Linux. This approach gives you significant control over your computer, while also enabling use of the Shim-dbx, which is described later, in Revoking Keys and Hashes.

If you decide to use outside keys, you should obtain them from their maintainer. For convenience, my rEFInd boot manager comes with a number of keys; see its git repository for easy access to individual keys. For better security, though, track down the original key and obtain it from a secure site. You'll need .cer, .der, or .esl files to add the key to your database. Copy any additional keys you obtain to the same FAT partition or USB flash drive to which you copied your own keys.

As noted earlier, the private keys are highly sensitive, so you should guard them carefully. Before locking them up, though, you'll want to use them to sign your binaries. This topic is up next....

Signing EFI Binaries

Once you lock down your computer with a new set of keys, it won't be able to run any programs that were not signed by one of the keys corresponding to the public db keys you've installed. Therefore, you'll probably want to sign your most important EFI programs before proceeding. (This won't be necessary if your EFI binaries and kernels are all signed by your distribution's maintainer and if you add the distribution's public key to your db.) Depending on your boot loader, you may need to sign your Linux kernels, too. (If you run into problems, you can always disable Secure Boot temporarily to sign more binaries, or use another computer to sign EFI/BOOT/bootx64.efi on a USB flash drive.)

In any event, the procedure to sign an EFI binary is fairly straightforward, once you've installed the sbsigntool package and created keys:

This example signs the vmlinuz.efi binary, located in the current directory, writing the signed binary to vmlinuz-signed.efi. Of course, you must change the names of the binaries to suit your needs, as well as adjust the path to the keys (DB.key and DB.crt). The DB.key and DB.crt filenames correspond to the database keys, described earlier. If you're signing a binary that should be recognized by Shim through MOK, you must change the key files appropriately.

This example shows two warnings. I don't claim to fully understand them, but they don't seem to do any harm—at least, the Linux kernel binaries I've signed that have produced these warnings have worked fine. (Such warnings seem to be less common in 2015 and later than they were a couple of years before then.) Another warning I've seen on binaries produced with GNU-EFI also seems harmless:

On the other hand, the ChangeLog file for GNU-EFI indicates that binaries created with GNU-EFI versions earlier than 3.0q may not boot in a Secure Boot environment when signed, and signing such binaries produces another warning:

If you see a warning like this, you may need to recompile your binary using a more recent version of GNU-EFI.

If you're using rEFIt, rEFInd, or gummiboot/systemd-boot, you must sign not just those boot manager binaries, but also the programs that they launch, such as Linux kernels, ELILO binaries, and filesystem drivers. If you fail to do this, you'll be unable to launch the boot loaders that the boot managers are intended to launch. Stock versions of ELILO, GRUB Legacy, and older builds of GRUB 2 don't check Secure Boot status or use EFI system calls to load kernels, so even signed versions of these programs will launch any kernel you feed them. This defeats the purpose of Secure Boot, though, at least when launching Linux. Most recent versions of GRUB 2 communicate with Shim or the Secure Boot subsystem for authenticating Linux kernels and so will refuse to launch a Linux kernel that's not been signed.

Once you've signed your binaries, you should install them to your ESP as you would an unsigned EFI binary. Signed binaries should work fine even on systems on which you've disabled Secure Boot. If your computer is already booting through an existing boot program such as GRUB or rEFInd, you must sign the binary with your own key and then either replace the original file or create a new boot entry by using efibootmgr or a similar tool. If you're currently booting in Secure Boot mode via Shim, you can either sign the Shim binary (leaving the follow-on boot loader untouched, at least initially) or sign the follow-on boot loader and register it to boot directly via efibootmgr. Similar comments apply if you're using PreLoader—but be aware that if you sign the follow-on boot loader, that will change its hash, so PreLoader will no longer recognize it as valid.

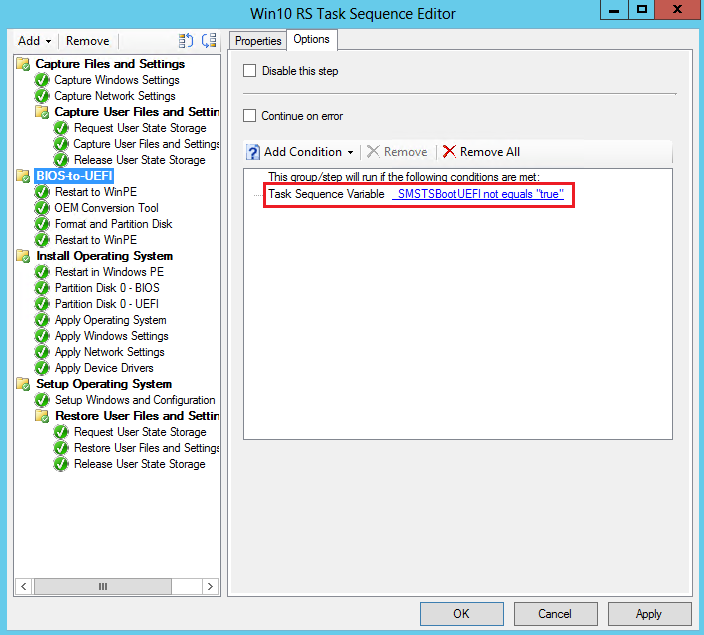

Securing One Computer

You can lock down a single computer with your new Secure Boot keys in any of three ways: You can use your firmware's built-in setup utility, you can use the KeyTool program that's part of the efitools package, or you can create a version of the LockDown program with an embedded key. The first of these methods is not possible on some computers, since many lack the necessary user interface options. Thus, using KeyTool is the most general-purpose method. Using LockDown also works, but it requires compiling the software from source. As this method can greatly simplify the setup of multiple computers, I describe it in more detail in that context.

Conceptually, replacing your default Secure Boot keys requires entering setup mode. In this mode, you may replace all of the keys, including the PK. Setup mode may be entered only from the firmware setup utility; you cannot enter setup mode from within an OS. Thus, you must deal with your computer's setup utility. Unfortunately, there is no standardization of UEFI user interfaces, so it's impossible to describe precisely how to enter setup mode in a way that applies to all computers. In fact, many UEFIs don't even refer to setup mode as such—they use some other term!

Replacing Keys Using Your Firmware's Setup Utility

Some UEFIs provide the means to install your own keys using their own built-in user interfaces. This method of doing the job is likely to be slightly easier than using a separate utility, because you won't need to use an EFI shell or otherwise configure such a tool to run; but all four of the interfaces I've seen employ confusing terminology and are unintuitive in certain key respects. They're all similar to one another, so for the sake of simplicity I'll describe only one: The ASUS P8H77-I, which was among the first motherboards to support Secure Boot, from around 2012. Thus, some of this computer's Secure Boot terminology is awkward; but full-featured modern boards don't differ greatly from this one.

To begin, you must find a way to enter the firmware setup utility. You can do this by hitting the Delete or F2 key on many computers just after you power them on, but this detail varies greatly between machines. Check your manual or watch the screen for prompts. Many Linux boot managers, including my own rEFInd, offer options to launch the firmware setup tool, so you may be able to use that method, too—but this feature relies on firmware support that's not universal, so it might not work for you. This same firmware support can be accessed from within an OS. In Linux systems that use systemd, typing systemctl reboot --firmware will do the job.

Once you've entered the firmware setup utility, you must find the Secure Boot options. In the case of the ASUS P8H77, you may need to hit F7 to enter Advanced Mode, select the Boot screen, and then scroll down to the Secure Boot option, as shown here:

Entering the Secure Boot menu, set OS Type to Windows UEFI mode. (Most computers use a more sensible name, but in 2012, ASUS seemed to think that Secure Boot was a Windows-only feature.) This will activate another submenu called Key Management. As you can see from the following screen shot, this menu provides options to clear keys, save keys, and modify the PK, KEK, db, and dbx individually. (The dbx options require scrolling down on this computer.)

Before proceeding, you might want to select the Save Secure Boot keys option, which saves your keys to disk files. The ASUS permits to you restore the default keys, so this isn't really vital if you're starting from the factory defaults with this model; but if yours doesn't offer such a reset-to-defaults option or if you've modified the keys, saving them may be prudent.

In the case of the ASUS P8H77-I, you enter setup mode by selecting the Clear Secure Boot keys option. (Many computers enter setup mode in an analogous way.) As the name implies, this option also erases all your Secure Boot keys. (It does not erase your MOKs, though.) You can then use the Load... from File and Append... from File options to load the files you prepared earlier. I recommend starting with the db, then installing your KEK, and finishing with the PK. The reason is that some systems exit setup mode the moment you enter a new PK, so doing the PK last is necessary. (The ASUS isn't so finicky, though.) If you want to load multiple keys (say, your own and the key for your Linux distribution), be sure to select the Append db from File option for the second and subsequent keys, since the Load... option deletes the current keys of that type.

The ASUS P8H77-I's prompts are confusing once you opt to load or append a key from a file. The first prompt is Append the additional db, with a yes/no option. What the firmware is really asking is whether you want to load the default keys. If you respond yes, you won't be prompted to access a file and the default keys will be added to the db. Making this mistake after you've loaded two or three keys from files can be quite frustrating! When you respond no to the query, you'll be shown a primitive file selection dialog box, with which you can navigate your disks to locate a suitable key file.

In this case, a 'suitable key file' is a .cer/.der or .esl file. (I've seen reports of UEFIs that require .auth files for this purpose.) The ASUS will ask whether the file is a key certificate blob or a Uefi secure variable. The former refers to .cer/.der files and the latter refers to .esl files.

After you've loaded one or more db keys, one or more KEKs, and your PK, you can hit F10 to exit and save your changes. If you prepared your keys properly, signed your boot loader properly, and (if applicable) registered your boot loader via efibootmgr, you should see your boot loader appear. It should continue to launch anything that you've signed with your key and refuse to launch anything that's not signed. An exception is boot loaders such as ELILO, GRUB Legacy, and early versions of GRUB 2, which don't check Secure Boot signatures on kernels. Also, if you signed a Shim or PreLoader binary and boot through it, anything authenticated by Shim or PreLoader should launch.

Replacing Keys Using KeyTool

Even if you can't find a Secure Boot key management screen like the one I've just described, you can perform similar tasks by using the KeyTool binary that comes with efitools. The procedure is as follows:

- Configure KeyTool to launch—You can launch KeyTool in any number of ways. Examples include:

- Copy KeyTool-signed.efi to a FAT USB flash drive under the filename EFI/BOOT/bootx64.efi. You'll then be able to boot from the USB flash drive as you would from an OS installation medium.

- Configure your system to boot an EFI shell, and then launch KeyTool from it. If you can already launch a shell from your firmware or from a boot manager, this is a simple solution, since you need only copy KeyTool-signed.efi to your ESP.

- Copy KeyTool-signed.efi to your ESP and register it as a boot option with efibootmgr; or create an entry for it in your rEFInd, GRUB, gummiboot/systemd-boot, or other boot manager menu.

- Launch KeyTool—Using whatever method you chose in step #1, launch KeyTool. The result should resemble the following:

- Save keys—Using the Save Keys menu option, save your existing keys. As with the method that uses the firmware's user interface exclusively, this step is a precaution that may not be necessary with your computer; but it's better to be safe than sorry.

- Enter setup mode—Reboot and enter your firmware's setup utility, as described earlier, in Replacing Keys Using Your Firmware's Setup Utility, and peruse the options to locate one to enter setup mode. Unfortunately, the name and location of this option is likely to be variable. It may be described as an option to remove the Secure Boot keys. The option may also be inactive or even invisible until you've activated Secure Boot. After you've selected the setup mode option, save your changes and reboot.

- Launch KeyTool—Launch KeyTool again.

- Verify setup mode—In the preceding screen shot, note that KeyTool is reporting that the computer is running in setup mode. If KeyTool reports something else, go back into your firmware's setup utility and try again to locate the correct option.

- Delete unwanted keys—If your firmware did not delete all your keys, you can use the Edit Keys menu to delete the ones you don't want. You should almost certainly delete the PK, and you may want to delete your KEKs and db entries. If you want to continue booting Windows, though, you can leave the Microsoft production PCA key intact; and if you want to continue booting programs other than the Windows boot loader that were signed by Microsoft, leave the Microsoft UEFI third-party marketplace key intact. Note that you can delete MOKs with KeyTool. If you're switching from a Secure Boot setup that used Shim or PreLoader, you might consider doing this—or you can save it until after you've tested your new configuration.

- Add new keys—The Add New Key item in the Edit Keys menu, unsurprisingly, enables you to add new keys. You'll have to browse your disks (identified by long and awkward EFI identifier strings) to locate your keys and add them one at a time. Be sure to enter the PK last; once it's entered, KeyTool will prevent additional changes except from .auth files. (I describe them in more detail shortly.) You can use .esl or .cer files for db and KEK entries. The .esl files will appear in the KeyTool menu with the GUID associated with them; but .cer files will show up with an ID of G0. (Note that KeyTool ignores .der files, so if you have keys with this filename extension, you must rename them to end in .cer.) When you enter the PK, you must select the PK.auth file. The mkkeys.sh script saves the GUID embedded in the .esl and .auth files it generates so that you can use them in the future, should the need arise. The GUID is stored in the myGUID.txt file. Note also that if you use your firmware's setup utility to enter your keys, it will use its own GUID.

- Exit and reboot—Use the Esc key to back out to the main menu, exit the program, and then reboot the computer.

With any luck, Secure Boot will now work with your new set of keys. Test it by launching programs or kernels that you have and have not signed. If it doesn't work as you expect, you can go back in and change your keys. To make changes, you must either use .auth files for the keys you want to load or load the noPK.auth file into the PK position, as described shortly. You might also want to check that Secure Boot is active in your firmware; some computers may drop back to leaving Secure Boot disabled after you're done with KeyTool.

After you've locked down your platform with KeyTool, it won't permit you to make any additional changes from the .esl or .cer files in which the original keys were stored. It should, however, permit you to use .auth files to make changes. These files are basically .esl files that have been signed by the next-higher-level key—db files are signed with the KEK and KEK files are signed with the PK. The PK can sign itself, though. The command to sign a file looks something like this:

This example signs the mykey.esl db file with the KEK, saving the result as mykey.auth. You should then be able to load mykey.auth into the db using KeyTool, even when not in setup mode.

A particularly useful special .auth file is noPK.auth. Both the efitools build process and my mkkeys.sh script create this file, which removes the PK from your computer, returning it to setup mode without deleting your KEK, db, dbx, or MOK. The file must be matched to the original PK; you can't use the noPK.auth file you generate to remove the computer's original PK, or a different PK you generated some other time. Returning to setup mode in this way might be helpful if you must load keys that aren't already signed and turned into .auth files themselves. Remember to load the original PK.auth file after you've made your changes.

Be aware that KeyTool is very finicky about its .auth files. In part, this is because it checks not only the keys, but the GUIDs that are embedded in .esl (and hence .auth) files. If the GUID of the KEK used to sign a db key (or of the PK used to sign a KEK or PK) doesn't match that of the current KEK (or PK), KeyTool will refuse to make a change.

I've found that KeyTool can work differently on different computers. The instructions presented here for use of .auth files work fine on some machines, but fail completely on others. If you run into problems, I recommend saving your key files, using the firmware's own user interface to enter setup mode, restoring the db and KEK files you just saved, making whatever changes you intended, and then restoring the PK. This workaround is awkward, but it should do the trick. (Note that when you save existing keys, all the db keys will be stored in a single .esl file, even if you've entered several keys manually to start. This fact can greatly speed up recovery or replication of a configuration.)

One of the advantages of KeyTool, at least over the built-in setup utilities I've seen, is that it enables you to view and delete individual keys. This can be handy if you want to fine-tune your system without ripping everything out and starting from scratch.

Securing Multiple Computers

If you've read the preceding two sections, and if you need to replace the keys on a large number of computers, you may be groaning inwardly right now. Both of the preceding procedures involve a lot of tedious manual operations, so you'll end up spending several minutes per computer—and the possibility of error when selecting keys is significant.

Fortunately, there is an alternative that can help remove some (but not all) of the tedium and reduce the risk of making a mistake. The efitools package ships with an EFI program called LockDown, which automates the process of installing keys. Unfortunately, the keys it installs are stored in the binary itself, which means that you must compile the program yourself for it to do you any good. If you're unfamiliar with building software in Linux, you may run into significant stumbling blocks in the following procedure; describing every possible problem and solution is beyond the scope of this page. The procedure to build the program is as follows:

- Prepare a Linux computer for building software, and especially for building EFI software. Some distributions provide a meta-package that can help, such as build-essential in Ubuntu. You'll also need the gnu-efi and git packages, and perhaps some others.

- Download the efitools source code. Typing git clone git://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/jejb/efitools.git in a scratch directory should do the trick.

- Change into the efitools directory.

- Type make. After a few seconds, this process should complete. The last few lines look like this:If you see an error message instead, you'll have to debug the problem. It may be caused by a missing tool, and in most such cases an error message will contain a clue about what's missing, although such clues are seldom explicit—that is, they don't usually read 'install the gnu-efi package to continue,' although they may refer to missing header files that, if you Google their name, will point you to gnu-efi.

Assuming no errors, you should now have a number of files, including public and private keys and the LockDown.efi binary. There is, however, one potential complication: The build process for the program generated its own keys. This may be fine; if you want to simply use your own keys and no others, or if you're happy to sign a version of Shim or PreLoader and use MOKs to launch other EFI programs, you can store the PK, KEK, and db files that the build process generated and use the db files to sign your own binaries.

On the other hand, if you want to include keys for your Linux distribution, for Microsoft products, or for some other party, using the LockDown binary generated at this point will be inadequate. Fortunately, there is a way to include additional keys in the binary:

- If you haven't already built efitools, do so by typing make in the efitools directory.

- If you want to use keys you've built with mkkeys.sh, copy all of the files that mkkeys.sh created to the efitools source code directory (the same directory that holds LockDown.c and other .c files for the EFI binaries).

- Copy any third-party public keys you want to include, such as Microsoft's or your distribution's public keys, to the efitools source code directory.

- Convert all the additional keys you want LockDown to install into .esl format. If you have .crt files, each one can be converted as follows:Change mykey.crt to the original key's filename and mykey.esl into a matching .esl filename. You may also need to change python3 to python or python2. If you have .cer or .der files, they must first beconverted to .crt form:

- Concatenate all the .esl files that are destined for the db:

- If you want multiple KEKs in your final system, repeat the previous two steps for the KEKs.

- If you want to use a PK you generated or obtained in some way, rather than the one created by efitools, you must obtain or generate a PK.esl file, much as you did for DB.esl.

- Remove the version of LockDown that's already been built, including its intermediate files:

- Type make to build a copy of LockDown that includes all the keys you've placed in DB.esl (and in KEK.esl, if you've added keys to it).

With your LockDown.efi binary in hand, you can use it to (relatively) quickly install your custom set of keys on a computer. The procedure bears some similarities to that used to set up a computer using the built-in setup utility or KeyTool; however, you must enter setup mode and then run LockDown.efi. (Installing it to run from a USB flash drive can be a good way to move it around efficiently to set up many machines.) When you run LockDown.efi, it should report something like the following:

Some computers don't switch immediately to Secure Boot mode when LockDown runs, in which case the final line will report that the computer is not set to boot securely. This is not necessarily cause for concern; when you reboot, the computer may activate Secure Boot, and if it doesn't, you should be able to use the firmware's own user interface to do so.

The build process for efitools creates both signed and unsigned versions of several other programs. You can use one matched pair of them, such as HelloWorld.efi and HelloWorld-signed.efi, to test that LockDown did what it should. If you replaced the keys with your own, though, you may need to rebuild this program just as you did LockDown.

Managing Keys from Linux

Once you've taken full control of your Secure Boot keys, you can manage them from within Linux. The efitools package provides two utilities to help with this task: efi-readvar and efi-updatevar. As their names imply, they're used to read and write, respectively.

To get an overview of your Secure Boot keys, you can simply type efi-readvar:

As you can see, this computer has one PK, one KEK, and three db entries. The PK, KEK, and first db entry were built with my mkkeys.sh script using the name Ringworld 2015-2-17. The second db entry is the public key associated with my rEFInd project, and the third is Canonical's public key. Although several of my computers have MOKs, they haven't shown up in efi-readvar output for me.

You can limit efi-readvar's output by applying the -v and -s options; see the program's man page for details. The -o option redirect's output to a file.

The efi-updatevar command is more complex. You can use it to update your db or KEK database, but only if you have the private key for the next-higher database—that is, to add a db entry, you need the KEK private key, and to add a KEK, you need the PK private key. Thus, efi-updatevar is likely to be useful only if you've taken full control of the computer's Secure Boot keys, as described earlier on this page. The command to add a db key would look like this:

In practice, this command might not work immediately, even if you have the correct key files and apply them appropriately. Specifically, efi-updatevar may report Failed to update db: Operation not permitted or Cannot write to db, wrong filesystem permissions, even when run as root. The reason is that this command relies on write access to the EFI firmware variables at /sys/firmware/efi/efivars/, and most Linux distributions mount this pseudo-filesystem such that the immutable bit is set on most files, as a precaution against damage. To check the status of this bit, use the following command:

In this example, the db, dbx, KEK, and PK are all immutable, as revealed by the i character in the fifth position of each line of output. To change this setting, you can use chattr to remove the immutable flag:

Note that, although you can discover the immutable flag status of most Secure Boot files (the dbx being an exception on some distributions) as an ordinary user, you can change it with chattr only as root (or using sudo). Once you've removed the immutable flag, it should be possible to use efi-updatevar to update the EFI variables. Once you've done so, I recommend re-setting the variable by using chattr with +i rather than -i. (The values will usually end up being reset when you reboot, though, so this precaution may be redundant if you reboot immediately to test the changes.)

For more information on this tool, read the efi-updatevar man pages and its author's blog posts on the tool.

Revoking Keys and Hashes

As described earlier, Secure Boot uses several key databases. One of these, the dbx, holds a list of keys and hashes that are not to be trusted; if an item appears in the dbx, it will be prevented from running, even if it would otherwise be granted access because of a db entry. On most computers, the dbx is effectively controlled by Microsoft, because adding entries to the dbx can be done only if the item to be added is signed by a private KEK that matches the public KEK stored in NVRAM, and that key in turn is normally Microsoft's. (Some computer manufacturers include their own key here, too, so they can add items to the dbx.)

Of course, if you take full control of your computer's Secure Boot process, it will be your key in the KEK, so it will be you who can manage the dbx. If you leave Microsoft's key in the KEK, too, then Microsoft will be able to add items to the dbx, if you boot Windows or if a non-Windows OS adds items signed by Microsoft.

This has become particularly relevant in 2020 and early 2021 because of security bugs discovered in GRUB 2. The first of these bugs is known as the Boot Hole, but that discovery spurred careful scrutiny of GRUB 2 and the discovery of a total of eight GRUB 2 bugs. Because so many GRUB 2 binaries have been released by so many Linux distributions, adding all of these binaries to the dbx of all computers with Secure Boot enabled is impractical; doing so would consume too much NVRAM, which is a scarce resource. (Even so, a large number of dbx entries related to this problem have been pushed out by Microsoft.)

As described on the previous page, the solution for computers with conventional Secure Boot configurations has been to add a dbx-type database to Shim itself, and to add older Shim binaries' hashes to the dbx, rather than hashes for the more numerous GRUB 2 binaries. This solution works for conventional configurations, but how does it impact you if you've taken control of your Secure Boot keys? The answer depends on the details of what you've done.

If you've excised all third-party keys from your computer, then you're only slightly affected; your computer won't run any Shim signed only by Microsoft or any GRUB 2 signed only by a distribution maintainer, as per your intent. In this case, you should update your GRUB 2 binaries to versions that are not affected by Boot Hole or related bugs, and ideally destroy any older binaries that you've signed in the past. If you wanted to be extra careful, you could generate new keys, replace your old keys with the new ones, and re-sign your latest binaries with the new keys. Also, remember that your own keys are only as secure as their storage; if you keep them unencrypted on your hard disk, then an intruder or malware can read them and sign whatever they like.

If you've added any third-party keys to your db, then your situation is more complex. The details depend on what third-party keys you've added and how you're booting Linux:

- Microsoft's root key — Microsoft uses this key to sign its own binaries, not Linux Shim binaries or GRUB 2 binaries. Thus, it doesn't play a role in the GRUB Boot Hole, and adding it, should you want to dual-boot with Windows, should not be a problem. (Of course, it's always possible that some other Microsoft-specific bug might create problems.)

- Microsoft's third-party marketplace key — If you've added this key, say to enable use of a plug-in video card or even to use Shim, then this creates a possible vulnerability. With this key in place, old Shim binaries signed by Microsoft's key will launch, and that Shim will in turn launch vulnerable GRUB 2 binaries — unless, of course, your dbx holds the necessary revocation keys or hashes. Updating your dbx to protect against this problem is described shortly.

- Distribution maintainers' keys — If you rely on distribution maintainers' keys to launch GRUB directly, thus bypassing Shim, then you won't gain the benefit of the new Shim-dbx feature. You can gain protection against some potential exploits by ensuring your UEFI dbx is up-to-date, but as Linux distributions increasingly rely on the Shim-dbx going forward, this approach will be increasingly ineffectual. Thus, if you use this approach, you should take extra care to ensure that your boot manager and boot loader binaries are up-to-date, and be alert to any suspicious changes in your boot process. A good case can be made for removing distribution maintainers' keys from your db and instead relying on Shim to launch your boot manager or boot loader. (You could sign this boot program yourself instead of relying on Microsoft's third-party marketplace key, if you want to keep it off your system; but you'll need to re-sign Shim whenever it's updated.)

- Other third-party keys — Keys used by third parties, including computer manufacturers and small developers (myself included) are potential sources of vulnerability. They don't pose any special risk with respect to the GRUB Boot Hole, since they haven't been used to sign GRUB 2 binaries, but in theory they could be exploited if they were to fall into the wrong hands.

Although the flurry of activity in 2020 and 2021 around the Boot Hole are specific to GRUB 2, in principle similar issues could exist in other pre-boot software, such as systemd-boot/gummiboot or rEFInd. These programs are less popular than GRUB 2 and so receive less attention, but they could harbor bugs that could affect their security. Of course, because they're less popular, they're less likely to be abused by attackers — but relying on this situation is basically 'security through obscurity,' which is not a good policy.

If your computer does not run Windows, or if it does but you've removed Microsoft's KEK, then it's up to you to add items to the dbx. Doing so is likely irrelevant if your db lacks third-party keys, but if you rely on such keys, you should keep your dbx up-to-date. You can find a dbx revocation list on the UEFI Forum's Web site, among other places. (As I type, the list for AMD64/x86-64/X64 architecture was last updated on October 12, 2020.) You may also be able to extract the dbx from a computer that runs Windows, using tools such as KeyTool; or you can check with your computer manufacturer, which may make a similar file available signed with their KEK. The dbxupdate_x64.bin file on the UEFI Forum's Web site is a signed signature list (.auth) file, but with a .bin filename extension. The easiest way to install it under Linux is to use the efi-updatevar utility, as root or using sudo:

Of course, change KEK.key with the filename (including path) to your own KEK.key, which you generated earlier, as described in Creating Secure Boot Keys. You may also need to use chattr to remove the immutable flag on /sys/firmware/efi/efivars/dbx-d719b2cb-3d3a-4596-a3bc-dad00e67656f, as described in Managing Keys from Linux.

Windows Efi Editor

If you can't or don't want to use efi-updatevar, then you may be able to update the dbx to incorporate the dbxupdate_x64.bin file (or another dbx file) using KeyTool or your firmware's own Secure Boot utilities. Depending on how you do this, the file might need to be renamed to have a .esl or .auth filename, or even to be re-signed with your own KEK. The latter task can be done with the following command:

You may need to change the path or filenames for KEK.key and KEK.crt. The process of adding the file to your dbx is similar to those described earlier, in Securing One Computer.

Using any of these procedures, be aware of the difference between adding dbx entries and replacing those entries. The dbxupdate_x64.bin file referred to earlier is intended to hold a complete set of dbx entries, and so should replace the existing dbx entries (if any are present). If you add the file, and if the computer already has a large set of dbx entries, you will be needlessly consuming NVRAM space with duplicate entries — possibly to the extent that you'll fill the computer's NVRAM and cause unpredictable problems. If you want to add more hashes or keys in addition to those included in an update file, you can do so after installing the major file.

Conclusions

Taking full control of your computer's Secure Boot keys is not for everybody; the process is tedious and error-prone. It has the potential, though, to improve your computer's security by ensuring that only boot loaders and kernels you have explicitly approved can run.

Go on to 'Repairing Boot Repair'

Efi Profile Editor Download

Return to 'Managing EFI Boot Loaders for Linux' main page

copyright © 2015–2021 by Roderick W. Smith

If you have problems with or comments about this web page, pleasee-mail me at rodsmith@rodsbooks.com. Thanks.

Return to my main Web page.

Fiery color management

Fiery® color management tools give you maximum control over color quality. ICC-based color management technology is integrated in every Fiery server and works directly with advanced controls in Fiery Command WorkStation®. Fiery Color Profiler Suite is integrated with the Fiery server to create best-in-class ICC output profiles for each substrate in a few simple steps.

Excellent out-of-the-box color

Fiery servers deliver professional color quality right out of the box. Easy-to-use tools ensure the accuracy and consistency every printing business requires. The latest Fiery digital front ends benefit from EFI's next-generation color profiling technology Fiery Edge™ which further enhances out-of-the-box results.

Dependable color accuracy

- Achieve the best match for logo and brand colors

- Shorten turnaround times by printing on multiple print engines capable of producing the same output

- Reduce job rejections with reliable reproduction of complex, graphically-rich content files

- Produce color to a specified standard at all times

All the tools you need to get your color right – Fiery Color Profiler Suite

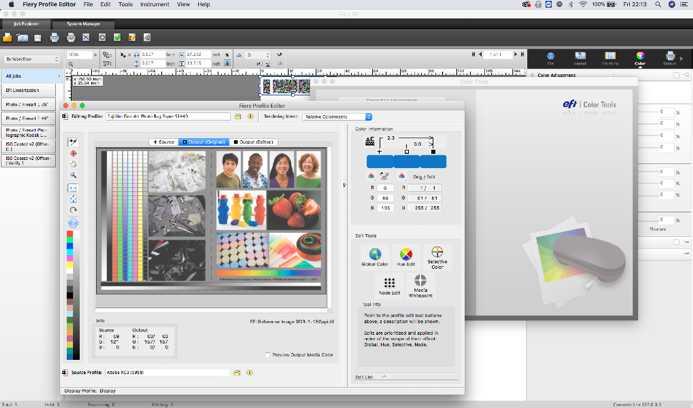

Fiery Color Profiler Suite offers a comprehensive set of market-leading color management tools that provide integrated color quality control at every stage of the printing workflow. Creating custom profiles using this technology ensures color reproduction is always accurate, consistent and reliable. It is the only profiling toolset on the market to integrate directly with both toner and inkjet Fiery servers. This seamless integration enables even a novice user to succeed at profiling a printer and paper combination, and then verifying the precision of color matching in just a few quick steps. It is also tightly integrated with Fiery Command WorkStation features such as Calibrator, Spot-On™ and Fiery ImageViewer. For users of the latest Fiery digital front ends, Fiery Edge profiling technology offers further user controls with Color Profiler Suite to enhance output such as boosting color saturation, and advanced black controls.

EFI offers a selection of spectrophotometers to precisely measure color with Fiery Color Profiler Suite in order to match industry color standards such as ISO, FOGRA and GRACoL (G7).

Fiery imaging technology

Fiery servers give you the highest level of performance and image quality, even on complex jobs with gradients, transparencies or overprints — even in VDP elements. The controls in Fiery Command WorkStation Job Properties provide complete access to all Fiery imaging features to ensure jobs print as the print buyer expects.

Exceptional image qualityEfi Profile Editor Free

- Automatic correction of potential mis-registration

- Smooth low-resolution images

- Sharpen and smooth black text and line art and minimize jaggies

- Eliminate “stair stepping” gradient shades in vector images

- Reproduce overprinted elements correctly

Efi Profile Editor Online

Easy image adjustments with Fiery Image Enhance Visual Editor

Easy image adjustments with Fiery Image Enhance Visual Editor- On-the-fly correction for individual images without modifying design files

- Manual controls also allow visual adjustment for:

- Brightness

- Contrast

- Highlights

- Shadows

- Color balance and skin tones

- Sharpness

- Red-eye